Description

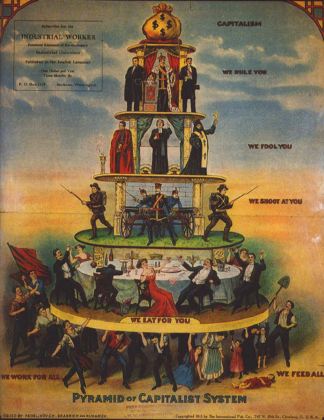

Welcome to Sociology 323: Economic Transformations in Capitalist Society

Lessons

Assignment Explanations

General Information

Class time: Thursday: 2:45PM-5:30PM

Class room: H 613 SGW

Office hours: Thursday: 5:45PM – 7:00PM (by request)

Office Location: H-556

Territorial Acknowledgement

I acknowledge that Concordia University is located on unceded Indigenous lands. The Kanien’kehá:ka Nation is recognized as the custodians of the lands and waters on which we gather today. Tiohtiá:ke/Montreal is historically known as a gathering place for many First Nations. Today, it is home to a diverse population of Indigenous and other peoples. We respect the continued connections with the past, present and future in our ongoing relationships with Indigenous and other peoples within the Montreal community. (Indigenous Directions Leadership Group, Feb. 16, 2017)

Course Description from Concordia Calendar

This course maps the emergence of capitalist society and its transformations over the 20th century, and also explores a number of its contemporary dynamics. The course takes a panoramic and integrated approach to the analysis of capitalist society, demonstrating the deep interconnectedness of what is referred to as “the economy” to all aspects of social life.

Course Description from Professor Erik

Global capitalism fosters practices that harm both society and the environment by externalizing costs to maximize profits. Classical, neo-classical, and neo-liberal economists have reinforced the belief that value is derived from resource extraction and that human activity is separate from nature—a concept known as the metabolic rift. This narrow focus on increasing production as a marker of economic success overlooks the destructive impact of relentless growth in a world with finite resources.

In this course, students will explore a range of economic perspectives to understand the root causes and consequences of the current ecological and social crises. By studying various political and economic philosophies, students will gain insights into transformative solutions to these issues. For example, they will examine non and alternative market methods of exchanging goods and services, such as reciprocity and redistribution. The course will also cover the intersections of political, economic, and social spheres to provide a holistic understanding of human activity, economies, and political power. Students will approach these topics from both macro and micro perspectives to analyze global and local economies. Additionally, they will critically assess the roles of firms and institutions in shaping economic practices, including work, leisure, consumption, energy use, sustainable development, resource management, trade, and waste management. Finally, students will reflect on their own participation in these economic practices and explore collective approaches to addressing current ecological challenges.

This course is designed to critically examine economics and explore alternatives to current political and economic systems. Students will start by learning foundational economic theories and concepts, such as defining economies, understanding economic systems, and using rudimentary economic terminology. They will compare and contrast traditional economics with emerging social and ecological economic perspectives. The course will trace the history of traditional economics and the evolution of social and ecological economics through various frameworks and contemporary theories. Key questions include: What differentiates ecological, social, and traditional economies? What is neo-liberalism, and how did it develop? Why has Gross Domestic Product (GDP) become a central measure of economic success for traditional economists? Students will also explore ecological boundaries, crises, and measurement indicators, along with the role of social inequality in addressing biophysical issues. They will consider questions such as: What global challenges are we facing? What are planetary boundaries, and how can we measure them to avoid tipping points? Who are the primary contributors to ecological degradation? In the latter part of the course, students will engage in an in-depth exploration of ethical economic practices, concentrating on three pivotal social-ecological alternatives: degrowth, diverse economies, and doughnut economics. They will explore questions like: How can we reintegrate economic systems into social and ecological contexts? How can we cultivate ethical economic practices? How can we prioritize values that promote sustainability rather than destruction? How can we shift away from measuring economic success by production growth and instead focus on thriving within ecological limits?

Students will critically reflect on how they participate in local and global economies throughout the course. They will also be encouraged to perform an action-research project to make ethical interventions to create better economic practices that include social justice, strong sustainability and decolonial perspectives.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of the course, the students will:

Recognize and understand desirable, viable and achievable alternatives to neo-liberal capitalism.

Articulate well-developed critiques of contemporary economics and prevailing economic systems.

Understand how to identify the causes and consequences of social and ecological problems and offer solutions to address these problems.

Develop a critical understanding of a plurality of economic approaches in relation to environmental and social problems.

Communicate the history and philosophies within the field of social and ecological economics.

Use the tools and language of diverse economies to explain contemporary environmental issues and concrete real-world cases.

Apply diverse economic approaches to imagine and create ethical economic conditions.

Move beyond understandings of weak sustainability towards more transformative approaches.

Incorporate social justice and decolonial perspectives in understanding social and ecological economics.

Perform action research to incorporate ontological approaches in creating new economic possibilities.

Understand how to re-embed economies into society and the biosphere.

Identify planetary boundaries and ecological crises.

Comprehend degrowth economic perspectives.

Understand doughnut economics.

Identify multiple forms of value and understand how to compare conflicting theories of value.

Instructional Method

This course will be conducted in person and structured as a seminar. Each class will begin with a short presentation and discussion led by Professor Erik, who will introduce key themes, provide additional examples, and offer critical perspectives on the weekly topics beyond what is covered in the readings. Students are expected to complete the required readings before class and actively engage in interactive activities and critical discussions. Assignments are designed to offer students critical perspectives on political economy, facilitate experiential learning through engagement with community members, and explore new political and economic possibilities through action research.

Required Course Materials

Students are required to complete the weekly readings before coming to class. Some weeks have more readings than others. For these weeks, Professor Erik will form smaller reading groups and assign different chapters to each group to ensure the readings are manageable. All the books have been reserved (or requested to be reserved) as an e-copy to be available online at the Concordia Library. In some cases, the books are only available in hard copy and must be obtained from the Concordia Library in person. In other cases, the Concordia Library is still processing the e-version, which should be available to students shortly.

Course Schedule, Readings and Seminar Questions | |||

Week | Date | Description | Readings Due (please complete the readings before class) |

1 | Sept 5 | Introduction to Course | No Readings |

2 | Sept 12 | Societies and Economic Systems | Read ONE of the following options:

1 – For Students Without Much Knowledge About Economic Systems: (I requested an e-version of the reading but was only granted a hard copy for the library) Introduction (pp. 1 – 14) Chapter 1: The Economy and Economics (pp. 15 – 30) Chapter 2: Capitalism (pp. 31 – 40) Chapter 3: Economic History (pp. 41 – 51) Chapter 4: The Politics of Economics (pp. 52 – 62) 2 – For Students with a Little Knowledge About Economic Systems: Chang, H. (2014) Economics: The User’s Guide (I requested an e-version of this book to be available at the Concordia Library. Hopefully, it will be made available soon). Chapter 1: Life, the Universe and Everything: What is Economics? (p. 15 – 22) Chapter 2: From Pin to PIN; Capitalism 1776 and 2014 (pp. 25 – 34). Chapter 3: One Fucking Thing After Another: What Use is History? (pp. 37 – 78) Chapter 4: Let a Hundred Flowers Bloom: How to “Do” Economics (pp. 81 – 122) Chapter 5: Dramatis Personae: Who are the Economic Actors? (pp. 124 – 144) 3- For Students Knowledgeable About Economic Systems: Polanyi, K. (1944 & 2001) The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time, Beacon Press (2001 version). (Language bias declaration: this text contains male language biases whereby; people are referred to as Man). (I requested an e-version of the reading but was only granted a hard copy for the library) Chapter 4: Societies and Economic Systems (pp. 45 – 58) Chapter 5: Evolution of the Market Pattern (pp. 59 – 70) Chapter 6: The Self-Regulating Market and the Fictitious Commodities: Land, Labour and Money (pp. 71 – 80) |

3 | Sept 19 | Food, Land and Social Reproduction | |

4 | Sept 26 | Diverse Economies | Introduction: An Economic Politics of Our Time (pp. 1 – 25) Introduction to The Handbook of Diverse Economies: Inventory as Ethical Intervention (pp. 1 – 24) |

5 | Oct 3 | The Economy and the Anthropocene | Read Option 1 and ONE Other Option (2, 3, 4, or 5) Option 1 (everyone must read): Option 2: Angus, I. (2016) Facing the Anthropocene: Fossil Capitalism and the Crisis of the Earth System Chapter 1 – A Second Copernican Revolution (pp. 27 – 37) Chapter 2 – The Great Acceleration (pp. 38 – 47) Chapter 3 – When did the Anthropocene Begin? (pp. 48 – 58) Option 3: Angus, I. (2016) Facing the Anthropocene: Fossil Capitalism and the Crisis of the Earth System Chapter 4 – Tipping Points, Climate Chaos and Planetary Boundaries (pp. 59 – 77) Chapter 5 – First Near-Catastrophe (pp. 78 – 88) Chapter 6 – A New (and Deadly) Climate Regime (pp. 89 – 106) Option 4: Chapter 4: Measurement of Essential Indicators in Ecological Economics (pp. 125 – 147) Option 5: Chapter 5 – Boundaries and Indicators: Capturing and Measuring Progress Towards an Economy of Right Relationship Constrained by Global Ecological Limits (pp. 148 – 189) |

6 | Oct 10 | Ecological Economics | Read at Least ONE of the Following Chapters Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist Introduction: Who Wants to be an Economist? (pp. 1 – 26) Chapter 1: Change the Goal – From GDP to the Doughnut (pp. 27 – 54) Chapter 2: See the Big Picture – From Self-contained to embedded Economy (pp. 53 – 80) Chapter 3: Nurture Human Nature – From Rational Economic Man to Social Adaptable Humans (pp. 81 – 110) Chapter 4: Get Savvy with Systems – From Mechanical Equilibrium to Dynamic Complexity (pp. 111 – 138) Chapter 5: Design to Distribute – From ‘Growth Even it Up Again’ to Distribute by Design (pp. 139 – 174) Chapter 6: Create to Regenerate – From ‘Growth Will Clean it Up Again’ to Regenerative by Design (pp. 175 – 206) |

7 | Oct 24 | Work on Final Project | |

8 | Oct 31 | Degrowth | Please read one of the following articles or you can still read a chapter from the book below. or Read at Least ONE of the Following Chapters or the Article Below The Future is Degrowth: A Guide to a World Beyond Capitalism Chapter 1: Introduction (pp. 1 – 35) Chapter 2: Economic Growth (pp. 36 – 74) Chapter 3: Critiques of Growth (pp. 75 – 177) Chapter 4: Degrowth Visions (pp. 178 – 211). Chapter 5: Pathways to Degrowth (pp. 211 – 250) Chapter 6: Making Degrowth Real (pp. 251 – 284). Chapter 7: The Future of Degrowth (pp. 285 – 298) |

9 | Nov 7 | Expanding the Commons | Read at Least ONE of the Following Articles Article 1: Article 2: Article 3: |

10 | Nov 14 | Alternatives to Capitalism and Work on Final Project | Olin Wright. E. (2021) How to Be An Anti-Capitalist in the 21stCentury, Verso. Preface (pp. xi – xiv) Chapter 1: Why be Anti-Capitalist? (pp. 1 – 22) Chapter 2: Diagnosis and Critique of Capitalism (23 – 36) |

11 | Nov 21 | Alternatives to Capitalism and Work on Final Project | Olin Wright. E. (2021) How to Be An Anti-Capitalist in the 21stCentury, Verso. Chapter 3: Varieties of Anti-Capitalism (pp. 37 – 64) Chapter 4: The Destination Beyond Capitalism: Socialism as Economic Democracy (pp. 65 – 94) |

12 | Nov 28 | Alternatives to Capitalism and Work on Final Project | Olin Wright. E. (2021) How to Be An Anti-Capitalist in the 21stCentury, Verso. Chapter 5: Anti-Capitalism and the State (95 – 118) Chapter 6: Agents of Transformation (pp. 119 – 132) |

Assignments

Participation: The participation grade is based on attendance, involvement in discussions, engagement in classroom activities and completion of supplemental tasks. Students are expected to attend the course regularly and actively participate in discussions, demonstrating that they have completed and understood the assigned weekly readings.

Blog Posts (Essays on Economic Transitions): Students will write a blog (essay) of approximately 600–1000 words on a topic related to economies and societies, degrowth, critiques of current political economy, land back, diverse economies, ecological economics, expanding the commons, and/or alternatives to capitalism, as covered in the course lectures and required readings. Although the format is a blog, the content must be based on research rather than personal opinion. To achieve an A grade, the blog must include references to at least eight reliable, valid, and credible sources in addition to the course readings. Students with production skills may choose to create a video or podcast instead of a blog; however, this alternative must be approved by Professor Erik beforehand.

Interview or Self-Reflection Assignment: Students will either conduct an interview with a community member involved in non-capitalist or alternative capitalist activities, including participation in social or solidarity economies, social reproduction, or organizing for social justice causes, or they can write a self-reflection if they are personally engaged in such activities. For the interview option, students should explore the participant’s motivations for seeking alternatives to capitalism, their social and economic values, the specific activities they are involved in, the problems they aim to address, and the solutions they pursue. Students should also inquire about lessons learned and gather advice on participating in non-capitalist or alternative capitalist practices. Following the interview, students will write a summary that integrates key insights from the discussion, connecting these ideas explicitly to the course material. For the self-reflection option, students who meet the criteria described above can reflect on their own experiences, motivations, values, and the lessons they’ve learned from engaging in non-capitalist or alternative capitalist practices. The self-reflection should also connect personal experiences to the course readings in the same way as the interview option.

Action Research Project Proposal: Students will collaboratively write a proposal for an action research project they wish to undertake, submitting it as a group. The proposal should include the following elements: (1) identification of the group they will collaborate with, the project they will develop, or a draft proposal for a literature review; (2) a detailed description of the project or paper; (3) a specific timeline outlining the project’s stages; (4) a summary of each group member’s roles and responsibilities; (5) and a connection of the project topic to the course readings and relevant social or economic issues. For literature reviews, an annotated bibliography is required.

Action Research Project: This assignment is designed to provide students with hands-on experience in learning about economic transitions by engaging with community members who are working to create ethical economies and/or advocate for social justice. Students will undertake an action-based research project, which may involve creating a new project, participating in an existing initiative, or writing an in-depth research report on a course topic (approved by professor Erik). The report will be submitted as a group; however, part of the evaluation will focus on individual contributions to the project.

Students must form a group; however, they may work with a group that already exists and/or create something with like-minded people outside the classroom. Within these groups, students will form clusters and contribute based on their expertise. For instance, a student with strong research skills might focus on the research aspects of the project, a student with media skills could develop media infrastructure, and someone with excellent interpersonal communication skills could serve as a mobilizer, among other roles. Evaluation will be based on the depth of each student’s involvement in the project, their deliverables, a clear report of their contributions, an oral presentation summarizing their role, and the connection between the project and the course material.

Evaluation

Name of Assignment | Due Date | % of final grade |

Participation | Ongoing | 15 |

Interview/Self-Reflection | October 24 | 25 |

Blog (short essay) | November 21 | 25 |

Project Proposal | November 4 | 10 |

Final Project | December 5 | 25 |

Grading System

A+ | 95 – 100 | B+ | 80 – 84.9 | C+ | 67 – 69.9 | D+ | 57 – 59.9 | F | 0 – 49 |

A | 90 – 94.9 | B | 75 – 79.9 | C | 63 – 66.9 | D | 53 – 56.9 | NR | No report |

A- | 85 – 89.9 | B- | 70 – 74.9 | C- | 60 – 62.9 | D- | 50 – 52.9 |

|

|

Extraordinary Circumstances

In the event of extraordinary circumstances and pursuant to the Academic Regulations, the University may modify the delivery, content, structure, forum, location and/or evaluation scheme. In the event of such extraordinary circumstances, students will be informed of the changes.

Class Cancelation

Classes are officially considered cancelled if an instructor is 15 minutes late for a 50-minute class, 20 minutes late for a 75-minute class, or 30 minutes late for longer classes.

Intellectual Property

Content belonging to instructors shared in online courses, including, but not limited to, online lectures, course notes, and video recordings of classes remain the intellectual property of the faculty member. It may not be distributed, published or broadcast, in whole or in part, without the express permission of the faculty member. Students are also forbidden to use their own means of recording any elements of an online class or lecture without express permission of the instructor. Any unauthorized sharing of course content may constitute a breach of the Academic Code of Conduct and/or the Code of Rights and Responsibilities. As specified in the Policy on Intellectual Property, the University does not claim any ownership of or interest in any student IP. All university members retain copyright over their work.

Behaviour

All individuals participating in courses are expected to be professional and constructive throughout the course, including in their communications.

Concordia students are subject to the Code of Rights and Responsibilities which applies both when students are physically and virtually engaged in any University activity, including classes, seminars, meetings, etc. Students engaged in University activities must respect this Code when engaging with any members of the Concordia community, including faculty, staff, and students, whether such interactions are verbal or in writing, face to face or online/virtual. Failing to comply with the Code may result in charges and sanctions, as outlined in the Code.

Late Assignment and Submission Policy

Unless you are given permission in advance, late assignments will not be accepted without adequate documentation of medical or personal emergencies. All assignments must be submitted in hard copy on the due date. Assignments that are received electronically will have 30% deducted from the grade of the assignment.

Academic Integrity

Academic integrity means that every student must be honest and accurate in their work. The Academic Code of Conduct includes rules and regulations students must follow. Unacceptable practices include the following

- Copy from ANYWHERE without saying from where it came.

- Omit quotation marks for direct quotations.

- Let another student copy your work and then submit it as his/her own.

- Hand in the same assignment in more than one class without permission.

- Have unauthorized material in an exam, such as cheat sheets, or crib notes. YOU DON’T HAVE TO BE CAUGHT USING THEM – JUST HAVING THEM WILL GET YOU INTO TROUBLE!

- Copy from someone else’s exam.

- Communicate with another student during an exam by talking or using some form of signals.

- Add or remove pages from an examination booklet or take the booklet out of an exam room.

- Get hold of or steal an exam or assignment answers or questions.

- Write a test or exam for someone else or have someone write it for you.

- Hand in false documents such as medical notes, transcript or record.

- Falsify data or research results.

PLAGIARISM: The most common offense under the Academic Code of Conduct (see link below) is plagiarism, which the Code defines as “the presentation of the work of another person as one’s own or without proper acknowledgement.”

This could be material copied word for word from books, journals, internet sites, professor’s course notes, etc. It could be material that is paraphrased but closely resembles the original source. It could be the work of a fellow student, such as an answer on a quiz, data for a lab report, or a paper or assignment completed by another student. It could be a paper purchased through one of the many available sources. Plagiarism does not refer to words alone. It can also refer to copying images, graphs, tables, and ideas. Plagiarism is not limited to written work. It also applies to oral presentations, computer assignments and artistic works. Finally, if you translate the work of another person into French or English and do not cite the source, this is also plagiarism. In simple words: DO NOT COPY, PARAPHRASE OR TRANSLATE ANYTHING FROM ANYWHERE WITHOUT SAYING FROM WHERE YOU OBTAINED IT!

Take care to inform yourself of the rules, regulations and expectations for academic integrity.